Tags

A Naturalist in New Zealand, Dr Mary Gillham, Horrible Horace, living dinosaur, Mary Gillham Archive Project, Rodger Blanshard, Sphenodon punctatus, Stephens Island, tuatara, Unique New Zealand fauna

A snippet from my volunteer work on the ‘Dedicated Naturalist’ Project, helping to decipher and digitise, record and publicise the life’s work of naturalist extraordinaire, Dr Mary Gillham.

On 13 May 1957, the day I turned one, Mary Gillham wrote in her New Zealand diary:

The 13th, not perhaps the most auspicious day on which to undertake the most hazardous voyage of my stay in NZ, but it proved a perfect day.

Mary was sailing to Stephens Island through the often turbulent waters of Cook Strait to spend a week with lighthousekeeper Rodger Blanshard and family, to continue her studies into the flora and fauna of New Zealand’s many islands. On this day, too, Mary met her very first dinosaurs, though she went on to write:

Horace, the lighthouse tuatara or dinosaural lizard for which these islands are famous, was not at home but we found plenty more up to 2’ 6” long, some of which we took inside and put in the sink to photograph next day.

And the next day:

… Then back to the house for Rodger to photograph me festooned about with tuataras which had spent an uneventful night in the sink.

So, what is a tuatara? Here’s a little of what Mary later wrote in her book A Naturalist in New Zealand:

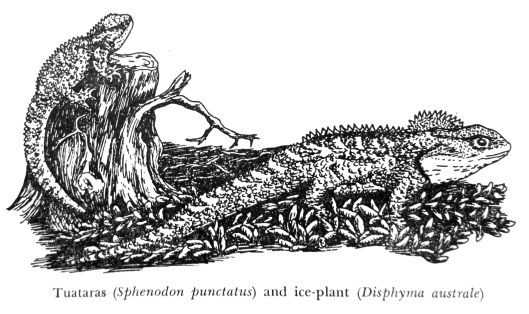

The reptile, whose full title is Sphenodon punctatus …

Its ancestors were Triassic and Jurassic saurians which, with the exception of Sphenodon, are thought to have died out 150 million years ago … a living fossil …

Its chief claim to fame is the vestigial third eye lying in a cavity in the top of the skull. This retains both retina and lens, but the retina is no longer able to reflect an image and its nerve supply degenerates as the animal grows. …

The lighthousekeepers of the various tuatara islands I visited took a proprietary interest in their tuataras and vied with each other to produce the biggest measurements – almost as if they were fish!

… live to a ripe old age; to such a ripe age in fact, that we mortals in our transience can barely keep account of it. Anyone who marks a young tuatara is unlikely to live long enough to record its decease.

… so the Blanshard family, who were on especially good terms with “Horrible Horace” the tuatara who lived in their woodpile. Numbers of Horace’s cronies dwelt within a few yards of the house …

I was surprised to learn that the dark warts with which they were beset were actually their own private brand of tick, Aponomma sphenodonti, and that the rusty patches on their flanks were untold numbers of minute red mites. Even these ancients are subject to the law that “great fleas have little fleas …”

Above left, a newspaper clipping of Mary and a tuatara, and, right, Mary’s photos of tuataras – and Rodger Blanshard – on Stephens Island.

For the full story about the Mary Gillham Archive Project, check out our website, and follow our progress on Facebook and on Twitter.

I now own a first edition copy of the book Naturalist in New Zealand, and look forward to reading it, one of these days 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe during the cold winter nights, sitting cosily by the fire with a mulled wine?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post on a creature that could pass for a miniature iguana, but happens to be more like a living fossil! I covered some of the ecology of New Zealand lakes in one of my blog posts, and it appears to be a very beautiful and environmentally sound habitat. I’d really like to visit there some day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, Jess. New Zealand is certainly a beautiful and ecologically interesting country, with a lot of unique flora and fauna. Most NZers are environmentally aware but, as in most countries, there is still a battle between big business, and sometimes government, wanting to make a profit and doing the right thing for the environment.

LikeLiked by 1 person